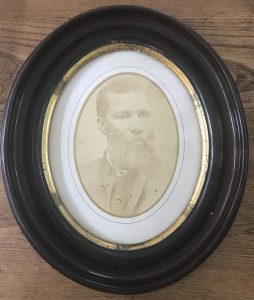

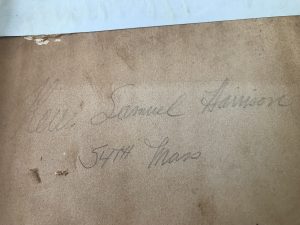

REV. SAMUEL HARRISON CHAPLIN 54TH MASS

Photograph of Rev. Samuel Harrison, in uniform as Chaplin. Circa 1863. 5 x 7 in. In Oval period frame.

An apparently unrecorded image. Harrison was an abolitionist, served as Chaplin of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the famous all black regiment. He was also instrumental in getting equal pay for black soldiers.

Samuel Harrison, was born into slavery in Philadelphia in 1818. He and his mother were freed in 1821. Shortly afterwards he and his widowed mother moved to New York City. When Harrison was nine years old, he returned to Philadelphia to live with an uncle.

Throughout his childhood, Harrison worked as an apprentice to his uncle in a shoemaking shop, learning a trade that would support him for years. He also attended church services with his mother regularly, and it was during his adolescence that Harrison decided to become a Presbyterian minister.

In 1836, Harrison enrolled in a manual school run by the abolitionist Gerrit Smith in Peterboro, New York. After only a few months, he transferred to the Western Reserve College in Hudson, Ohio (now Case Western Reserve University, in Cleveland, Ohio), an institution known for its abolitionist sympathies. Financial difficulties, however, forced him to return to Philadelphia in 1839.

In 1850 Harrison was ordained as a preacher by the Berkshire Association of Congregational Ministers and became the first minister of the Second Congregational Church of Pittsfield, the first black church founded in the county. His congregation was small but his work for black equality put him on the national stage. He was invited to speak at numerous churches in the region on contemporary political issues, such as blacks serving in the United States Army, war in Eastern Europe, and the history of the city of Pittsfield. In 1862 he lectured a Williamstown, Massachusetts congregation on The Cause and Cure for the War, a fiery oration in which he trumpeted support for enlistment of black troops.

Mass Governor John Andrew arrived in Pittsfield by train from Boston to visit the widow of Colonel Robert Shaw who died during the assault on Fort Wagner near Charleston SC. Colonel Shaw led the 1st and most famous all black infantry to fight in the Civil War, the 54th Mass Infantry that was immortalized in the 1989 Academy Award winning film “Glory”. During the Governor’s visit he called upon Harrison and asked him to go to South Carolina to express the sympathy of the Commonwealth over the tragic death of Colonel Shaw and that of nearly half the members of the regiment who died during the disastrous assault on Fort Wagner. Just 2 days before the tragedy a letter was sent from Governor Andrew’s Military Secretary to Colonel Shaw citing a “strong and unanimous” endorsement by the Governor of Mass, the President of Williams College, and highly respected clergy and laymen of Western Mass for Rev Harrison as the 1st Chaplain of the Mass 54th. Rev Harrison reported for commissioning and duty at Morris Island, SC and states in his autobiography that he was treated “in all respects…same as other chaplains of a fairer hue.”

But when payday came around “the paymaster refused to pay the men of the regiment the same amount paid to white troops because they were of African descent”. Harrison wrote, “Three months passed and no pay. I knew that my family’s means were nearly used up… My wife and six children, a debt of three hundred dollars on my house, and grocery bills. I had a hard burden to carry.” Chaplain Harrison filed a formal complaint to his superior officers, but to no avail.

Harrison wrote, “I grew sick under the pressure.” So sick was he that he requested and received a medical discharge during his 4th month of service. He thereupon complained to Mass Governor Andrew at being declined equal pay on account of his African ancestry.

Harrison’s demand that he receive the same pay as white chaplains led Governor Andrew and United States Attorney General Edward Bates to write letters to President Abraham Lincoln to end the discriminatory practice. In June 1864 legislation requiring equal pay, retroactive to January 1864, was passed in the army appropriations bill. Harrison states in his autobiography that it was suggested during his brief military service that he was “the victim” upon whom the whole matter of equal pay would turn and, as a consequence of the relationships he’d established with men of influence, that indeed was the case.